Eddy Edson

Well-Known Member

- Relationship to Diabetes

- Type 2

Big new multi-centre study, looking at infants through 95 year olds. Suprise: Metabolism generally doesn't change between ages of ~20 to ~60. And no general difference between men and women. (When controlled for body size and muscle weight.)

Energy needs shoot up during the first 12 months of life, such that by their first birthday, a one-year-old burns calories 50% faster for their body size than an adult.

And that’s not just because, in their first year, infants are busy tripling their birth weight. “Of course they're growing, but even once you control for that, their energy expenditures are rocketing up higher than you'd expect for their body size and composition,” said Pontzer, author of the book, “Burn,” on the science of metabolism.

An infant’s gas-guzzling metabolism may partly explain why children who don’t get enough to eat during this developmental window are less likely to survive and grow up to be healthy adults.

“Something is happening inside a baby’s cells to make them more active, and we don't know what those processes are yet,” Pontzer said.

After this initial surge in infancy, the data show that metabolism slows by about 3% each year until we reach our 20s, when it levels off into a new normal.

Despite the teen years being a time of growth spurts, the researchers didn’t see any uptick in daily calorie needs in adolescence after they took body size into account. “We really thought puberty would be different and it’s not,” Pontzer said.

Midlife was another surprise. Perhaps you’ve been told that it’s all downhill after 30 when it comes to your weight. But while several factors could explain the thickening waistlines that often emerge during our prime working years, the findings suggest that a changing metabolism isn’t one of them.

In fact, the researchers discovered that energy expenditures during these middle decades – our 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s -- were the most stable. Even during pregnancy, a woman’s calorie needs were no more or less than expected given her added bulk as the baby grows.

The data suggest that our metabolisms don’t really start to decline again until after age 60. The slowdown is gradual, only 0.7% a year. But a person in their 90s needs 26% fewer calories each day than someone in midlife.

Lost muscle mass as we get older may be partly to blame, the researchers say, since muscle burns more calories than fat. But it’s not the whole picture. “We controlled for muscle mass,” Pontzer said. “It’s because their cells are slowing down.”

The patterns held even when differing activity levels were taken into account.

For a long time, what drives shifts in energy expenditure has been difficult to parse because aging goes hand in hand with so many other changes, Pontzer said. But the research lends support to the idea that it’s more than age-related changes in lifestyle or body composition.

“All of this points to the conclusion that tissue metabolism, the work that the cells are doing, is changing over the course of the lifespan in ways we haven’t fully appreciated before,” Pontzer said. “You really need a big data set like this to get at those questions.”

Energy needs shoot up during the first 12 months of life, such that by their first birthday, a one-year-old burns calories 50% faster for their body size than an adult.

And that’s not just because, in their first year, infants are busy tripling their birth weight. “Of course they're growing, but even once you control for that, their energy expenditures are rocketing up higher than you'd expect for their body size and composition,” said Pontzer, author of the book, “Burn,” on the science of metabolism.

An infant’s gas-guzzling metabolism may partly explain why children who don’t get enough to eat during this developmental window are less likely to survive and grow up to be healthy adults.

“Something is happening inside a baby’s cells to make them more active, and we don't know what those processes are yet,” Pontzer said.

After this initial surge in infancy, the data show that metabolism slows by about 3% each year until we reach our 20s, when it levels off into a new normal.

Despite the teen years being a time of growth spurts, the researchers didn’t see any uptick in daily calorie needs in adolescence after they took body size into account. “We really thought puberty would be different and it’s not,” Pontzer said.

Midlife was another surprise. Perhaps you’ve been told that it’s all downhill after 30 when it comes to your weight. But while several factors could explain the thickening waistlines that often emerge during our prime working years, the findings suggest that a changing metabolism isn’t one of them.

In fact, the researchers discovered that energy expenditures during these middle decades – our 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s -- were the most stable. Even during pregnancy, a woman’s calorie needs were no more or less than expected given her added bulk as the baby grows.

The data suggest that our metabolisms don’t really start to decline again until after age 60. The slowdown is gradual, only 0.7% a year. But a person in their 90s needs 26% fewer calories each day than someone in midlife.

Lost muscle mass as we get older may be partly to blame, the researchers say, since muscle burns more calories than fat. But it’s not the whole picture. “We controlled for muscle mass,” Pontzer said. “It’s because their cells are slowing down.”

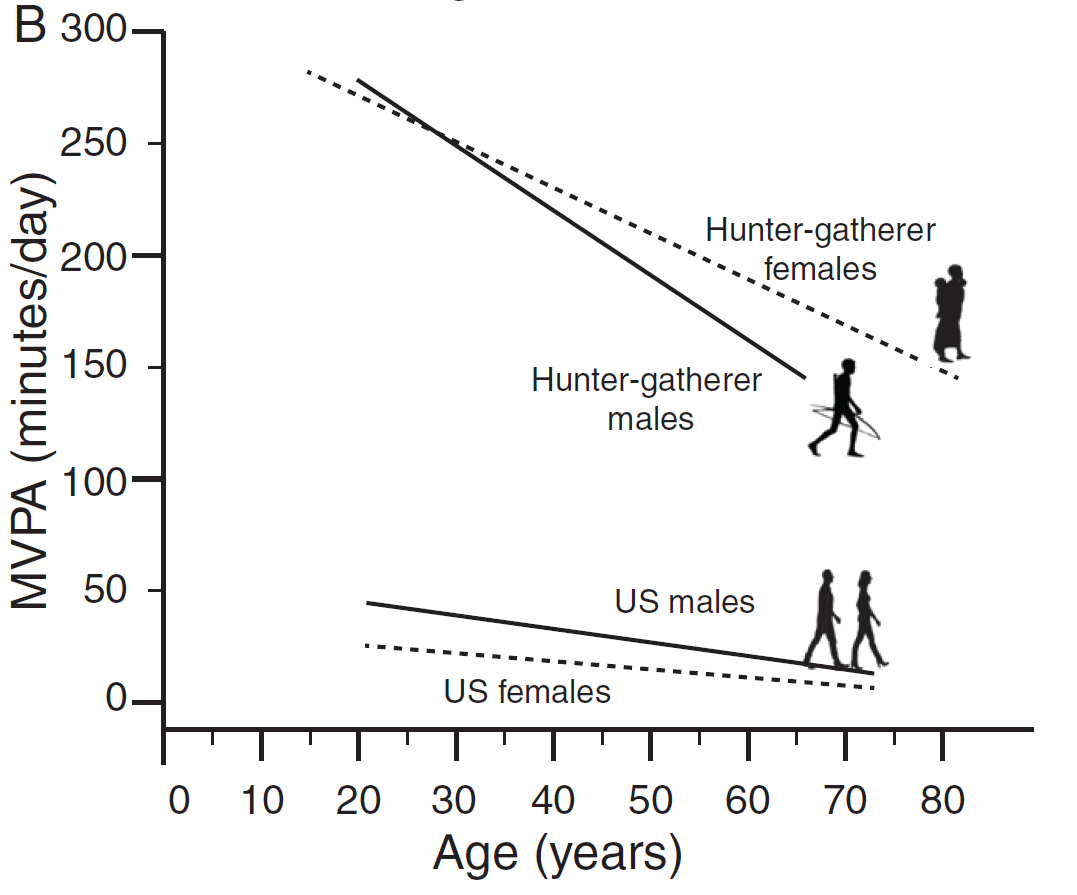

The patterns held even when differing activity levels were taken into account.

For a long time, what drives shifts in energy expenditure has been difficult to parse because aging goes hand in hand with so many other changes, Pontzer said. But the research lends support to the idea that it’s more than age-related changes in lifestyle or body composition.

“All of this points to the conclusion that tissue metabolism, the work that the cells are doing, is changing over the course of the lifespan in ways we haven’t fully appreciated before,” Pontzer said. “You really need a big data set like this to get at those questions.”