Eddy Edson

Well-Known Member

- Relationship to Diabetes

- Type 2

Lower energy intake observed in low-fat vegan vs. low-carb ketogenic diet

A cohort of adults had less energy intake when eating a low-fat, plant-based diet compared with an animal-based, low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet during a 2-week period, according to study data published in Nature Medicine.According to Kevin D. Hall, PhD, integrative physiology section chief at...

Effect of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake - Nature Medicine

In an inpatient, randomized controlled crossover trial, participants consumed 550–700 kcal day−1 fewer calories when following a plant-based, low-fat diet with a high glycemic load compared with an animal-based, low-carbohydrate diet with a low glycemic load; weight loss was comparable between...

Another study from Kevin Hall's group at the US NIH refuting the "carbohydrate-insulin model" for weight gain. That is, the Internet-popular theory that carbs make you gain weight by making you hungrier, because the additional insulin secretion which results from eating lots of carbs means that fats get retained, not burned, so your cells get starved & send "Eat more!" signals to yr brain or whatever.

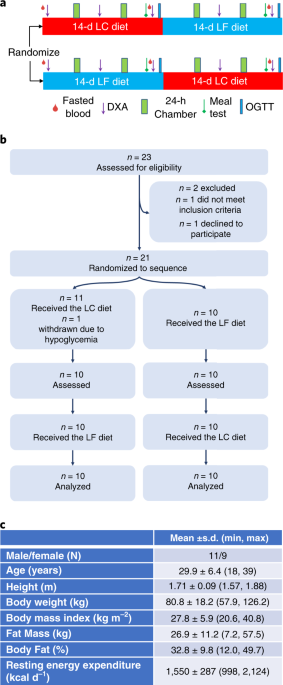

The carbohydrate–insulin model of obesity posits that high-carbohydrate diets lead to excess insulin secretion, thereby promoting fat accumulation and increasing energy intake. Thus, low-carbohydrate diets are predicted to reduce ad libitum energy intake as compared to low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets. To test this hypothesis, 20 adults aged 29.9 ± 1.4 (mean ± s.e.m.) years with body mass index of 27.8 ± 1.3 kg m−2 were admitted as inpatients to the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center and randomized to consume ad libitum either a minimally processed, plant-based, low-fat diet (10.3% fat, 75.2% carbohydrate) with high glycemic load (85 g 1,000 kcal−1) or a minimally processed, animal-based, ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet (75.8% fat, 10.0% carbohydrate) with low glycemic load (6 g 1,000 kcal−1) for 2 weeks followed immediately by the alternate diet for 2 weeks. One participant withdrew due to hypoglycemia during the low-carbohydrate diet. The primary outcomes compared mean daily ad libitum energy intake between each 2-week diet period as well as between the final week of each diet. We found that the low-fat diet led to 689 ± 73 kcal d−1 less energy intake than the low-carbohydrate diet over 2 weeks (P < 0.0001) and 544 ± 68 kcal d−1 less over the final week (P < 0.0001). Therefore, the predictions of the carbohydrate–insulin model were inconsistent with our observations.

In a randomised cross-over experiment, people ate more calories on a keto diet than on a low-fat high-calorie diet.

Hall noted that this study was not a weight loss study and that each diet resulted in some metabolic improvements in participants, and each may have its own uses for specific individuals.

“It’s not that one diet won over the other,” Hall said. “It’s that these simple models of what determines people’s food intake didn’t pan out, and in particular, the data was very clearly in the opposite direction of the carbohydrate-insulin model.”